Nowadays when we hear mention of disaster at sea, we might

think first of the loss of the Titanic or of environmentally damaging spillages

from huge oil tankers. Storm warnings mean falling trees, roads blocked,

flooding, power lines down. We probably donít think too much about ships at

risk. Enormous container ships can cope with the weather and there arenít as

many fishing boats as there once were. But it wasnít always like that.

In the days before HGVs and container ships goods were

transported internationally and round our coasts in smaller cargo ships which

were very vulnerable in bad weather. Over the centuries there were countless

wrecks and countless rescue attempts, with much loss of life. The first purpose

built lifeboat was launched in 1785, in the first half of the nineteenth century

the organisation which was to become the RNLI was established to provide a search and rescue service twenty four hours a day and

seven days a week, manned by volunteers who were usually fisherman or former

seamen. Over the following two centuries more than 600 of these volunteers have

lost their lives but never as many at one time as in the Mexico disaster off

Southport in 1886.

established to provide a search and rescue service twenty four hours a day and

seven days a week, manned by volunteers who were usually fisherman or former

seamen. Over the following two centuries more than 600 of these volunteers have

lost their lives but never as many at one time as in the Mexico disaster off

Southport in 1886.

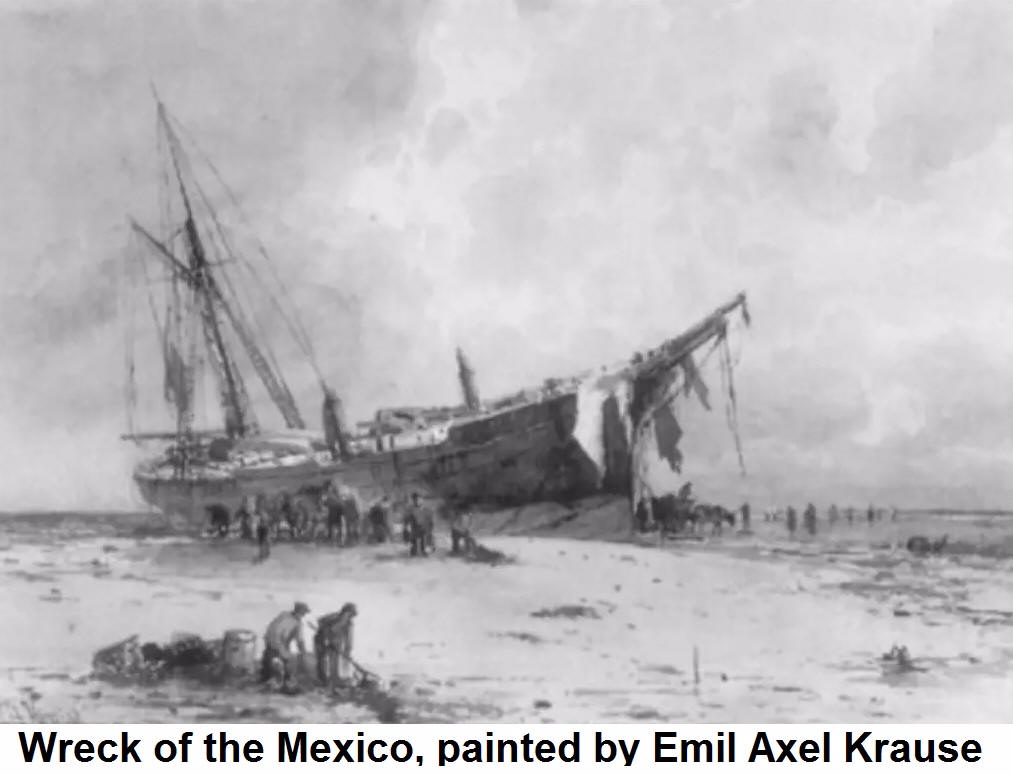

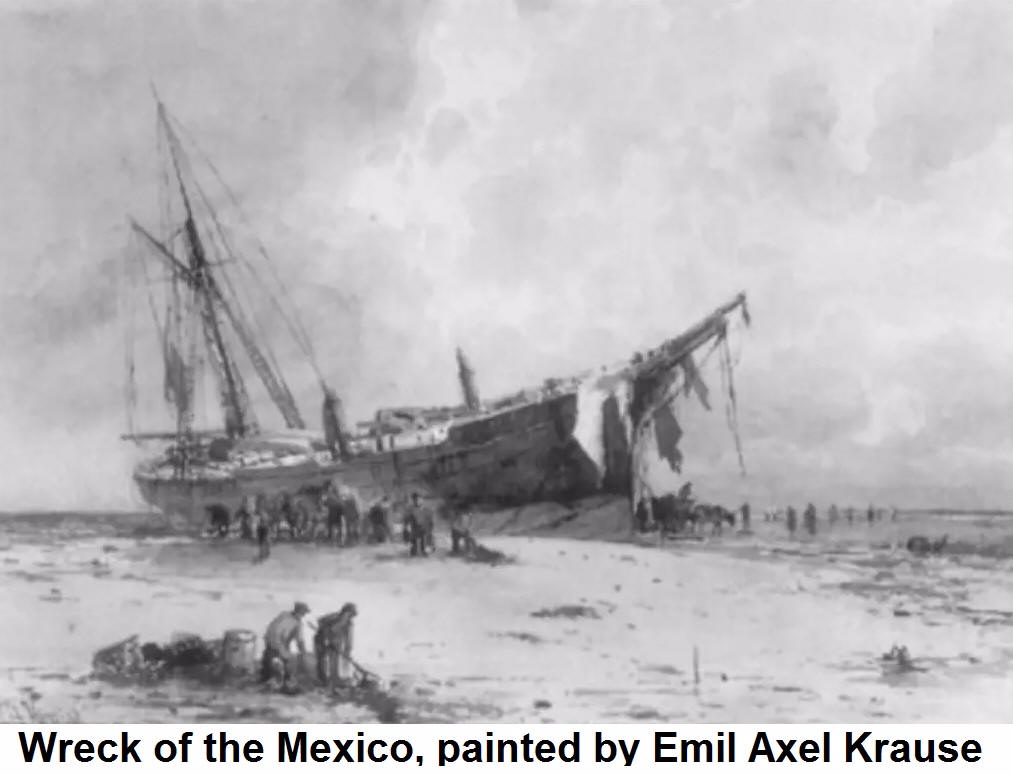

The Mexico was a German ship bound for Ecuador which had

set out from Liverpool on the 5th of December. A violent storm blew up as she

was passing Great Orme Head. She was badly damaged and blown off course towards

St Annes, then driven aground by heavy seas on to a sandbank in the Ribble

estuary.

On the evening of the 9th of December distress signals

were seen on shore and the Southport lifeboat, the Eliza Fearnley, was launched

with a crew of sixteen. She managed to reach the Mexico, but overturned in the

heavy seas before she could attempt a rescue. Two of the crew were trapped under

the boat but succeeded in freeing themselves and swimming to the shore to raise

the alarm. All of the others drowned. Not long after the Eliza Fearnley, the St

Annes  lifeboat,

the Laura Janet had also set out with thirteen men on board. They rowed out for

500 yards before hoisting their sails, the only driving force until the first

steam powered lifeboat in 1890. Boats had no motors until 1905. Despite the

weather, the Laura Janet is known to have reached two miles off Southport, but

nothing is known of her after that. The boat was found upturned the next morning

and all the crew were lost. Finally the new Lytham lifeboat, the Charles Biggs,

put to sea for the very first time. The crew rowed one and a half miles to the

Mexico where they found that the men had lashed themselves to the rigging for

safety. They got them off and brought them to the shore before the Mexico sank.

All her sailors survived. Twenty seven lifeboat men perished.

lifeboat,

the Laura Janet had also set out with thirteen men on board. They rowed out for

500 yards before hoisting their sails, the only driving force until the first

steam powered lifeboat in 1890. Boats had no motors until 1905. Despite the

weather, the Laura Janet is known to have reached two miles off Southport, but

nothing is known of her after that. The boat was found upturned the next morning

and all the crew were lost. Finally the new Lytham lifeboat, the Charles Biggs,

put to sea for the very first time. The crew rowed one and a half miles to the

Mexico where they found that the men had lashed themselves to the rigging for

safety. They got them off and brought them to the shore before the Mexico sank.

All her sailors survived. Twenty seven lifeboat men perished.

The loss of so many men aroused enormous public sympathy,

with a fund being opened to help the sixteen widows and fifty children left

without support. Donors included Queen Victoria and the German emperor and a

large sum of money was raised, some of it used to build memorials, the most

striking being the statue in St Annes of a lifeboatman looking out to sea. The

disaster also raised awareness throughout the country of the vital work of the

lifeboat service and the public began to recognise the need to support these

volunteers. In 1891 a Manchester man, Sir Charles Macara, organised Lifeboat

Saturday, a parade of bands, floats and lifeboats through the city, and the

first recorded street collection for charity took place. His wife went on to

form a Ladies Guild to organise further street collections and other fund

raising activities. Within ten years, there were forty Ladies Guilds all over

the country, doubling the income of the RNLI. Their work continues today to

raise the funds needed to support the work of the lifeboat service, which receives no government funding and which is still almost entirely staffed

by volunteers who risk their lives every time they put to sea.

which receives no government funding and which is still almost entirely staffed

by volunteers who risk their lives every time they put to sea.

While the tragic loss of the crews of the Southport and St

Annes lifeboats remains to this day the worst disaster in the history of the

RNLI, it also had a positive consequence in raising awareness of the work of

this vital service.

Libby Stone

established to provide a search and rescue service twenty four hours a day and

seven days a week, manned by volunteers who were usually fisherman or former

seamen. Over the following two centuries more than 600 of these volunteers have

lost their lives but never as many at one time as in the Mexico disaster off

Southport in 1886.

established to provide a search and rescue service twenty four hours a day and

seven days a week, manned by volunteers who were usually fisherman or former

seamen. Over the following two centuries more than 600 of these volunteers have

lost their lives but never as many at one time as in the Mexico disaster off

Southport in 1886.  lifeboat,

the Laura Janet had also set out with thirteen men on board. They rowed out for

500 yards before hoisting their sails, the only driving force until the first

steam powered lifeboat in 1890. Boats had no motors until 1905. Despite the

weather, the Laura Janet is known to have reached two miles off Southport, but

nothing is known of her after that. The boat was found upturned the next morning

and all the crew were lost. Finally the new Lytham lifeboat, the Charles Biggs,

put to sea for the very first time. The crew rowed one and a half miles to the

Mexico where they found that the men had lashed themselves to the rigging for

safety. They got them off and brought them to the shore before the Mexico sank.

All her sailors survived. Twenty seven lifeboat men perished.

lifeboat,

the Laura Janet had also set out with thirteen men on board. They rowed out for

500 yards before hoisting their sails, the only driving force until the first

steam powered lifeboat in 1890. Boats had no motors until 1905. Despite the

weather, the Laura Janet is known to have reached two miles off Southport, but

nothing is known of her after that. The boat was found upturned the next morning

and all the crew were lost. Finally the new Lytham lifeboat, the Charles Biggs,

put to sea for the very first time. The crew rowed one and a half miles to the

Mexico where they found that the men had lashed themselves to the rigging for

safety. They got them off and brought them to the shore before the Mexico sank.

All her sailors survived. Twenty seven lifeboat men perished.